Vargas Llosa, the Father of Anti-Fujimorism

<< Blinded by his militant and almost obsessive opposition to Fujimori, Mario Vargas Llosa had no qualms about supporting any candidate who stood against Fujimori or Keiko. Thus, he became the political godfather of Alejandro Toledo, Ollanta Humala, and...>>

https://500palabras.pe/en/opinion.php?opinion_id=46

Visitas: 204

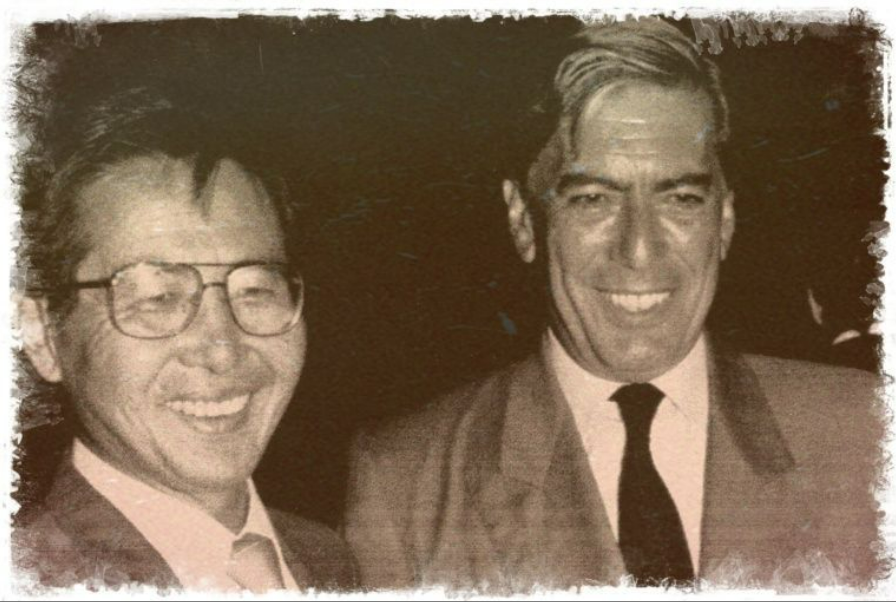

Once again, the excessive praise for Mario Vargas Llosa resurfaces, with people attributing to him a series of grand titles, qualities, and labels, such as “the most important political thinker in Latin America” (Iván Duque), “the greatest and most committed liberal voice we’ve ever had” (Jorge ‘Tuto’ Quiroga), “a fervent defender of the culture of freedom” (Eduardo Frei), and “the backbone of Latin American liberalism” (Andrés Pastrana), among others. It would probably be considered in poor taste to point out even a single flaw in the great Peruvian writer admired across the world. But no honest review of Mario would be complete without mentioning his fixations, obsessions, and inner demons that dominated him for many years, turning him into one of the most controversial figures in Peruvian politics — founder of pathological **anti-Fujimorism**, leader of the “Fujimori Never Again” movement, and patron of the “No to Keiko” groups. Though he himself did not march through the streets during those protests where some chanted insults at Keiko, his close associates did, including his wife and daughter. His protégé Pedro Cateriano acted as the Nobel laureate’s spokesperson and was in charge of fueling anti-Fujimorism during every electoral campaign. Blinded by his militant and almost obsessive opposition to Fujimori, Mario Vargas Llosa had no qualms about supporting any candidate who stood against Fujimori or Keiko. Thus, he became the political godfather of Alejandro Toledo, Ollanta Humala, and PPK, later defending Martín Vizcarra when he hastily dissolved Congress — supposedly to protect the Constitutional Court from the so-called “caviar elite.” At that point, Vargas Llosa set aside his unconditional support for democracy, which he had long preached around the world, to defend a president who showed authoritarian tendencies — all because of his deep-seated hostility toward Fujimorism. Just as one cannot deny Mario’s literary talent, one also cannot deny his ideological blindness, his obstinacy, and his fierce aversion to Fujimorism, which ultimately harmed the country. After more than two decades of preaching resentment toward Fujimorism and instilling in many Peruvians the belief that anything was better than Keiko, when the time finally came for the country to choose between Keiko and Pedro Castillo — an inexperienced and ill-prepared candidate surrounded by radicals — it was already too late. Mario was unable to persuade those he had once influenced through his rhetoric. His desperate efforts to ask people to vote for Keiko fell on deaf ears and even provoked mockery. Mario preferred to present himself as a radical democrat, condemning all dictatorships equally — as if they were the same, as if they had the same causes, duration, and consequences. For him, everything was black or white, with no nuance. Yet reality, especially political reality, is never that simple. In this respect, Mario chose dogmatism, ideological rigidity, and the posture of the untouchable, uncompromising democrat. My final impression is that Mario was always a *caviar* — a privileged intellectual who embraced progressive ideals. He never ceased to be Zavalita, his nearly autobiographical character from *Conversation in the Cathedral*: the upper-class Miraflores boy who rejects his privileged condition, struggles with his father, seeks to “proletarianize” himself, leaves the Catholic University to study at San Marcos among leftist radicals, and never finishes his degree. Arrested by the police and later rescued by his father’s political influence, he doesn’t thank him but resents him. As a social renegade, he distances himself from his family, takes a modest job at a newspaper, and becomes a writer. That, in essence, is Mario Vargas Llosa himself — a progressive intellectual from Miraflores who ended up as a globally renowned *caviar*. Personally, I value his literary legacy; I wouldn’t go as far as to praise him as a liberal thinker. That’s beyond my conviction.